The following first person narrative by Bill Armstrong covered a noteworthy flight of local aircraft to and from Oshkosh in 1990. Both of the authors of this book participated in this journey, accompanied by their sons:

The flight of four small aircraft that departed Cumberland, Maryland on the early morning of July 24, 1990 presented a wide spectrum of color amongst the similar slow flying machines as they headed northwest over the Appalachian Mountains. To a ground observer familiar with different types of aircraft, it was evident that all were high wing craft, powered by small engines as evidenced by the low sound, with vintage dating to the 1940’s. The lead aircraft displayed a black and white star burst design paint scheme, the second had a bright orange belly with the rest a brilliant yellow, the third a pleasant light blue and white, and the fourth totally yellow, the only one of a single color. The first three aircraft, Aeronca 7AC’s, more commonly known as ‘Champs’, all were manufactured in 1946 in Middletown, Ohio. The fourth, a Piper J-3 ‘Cub’, was built even earlier in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, at the Piper Aircraft factory. Both of these type aircraft were utilized for pilot training when initially produced and their use allowed a multitude of individuals to become aviators. Now, in these later years, the four aircraft were bound together by their owners and occupants with a common purpose.

Each aircraft was configured with a tandem seating arrangement capable of carrying two, with controls in each seat. In the cockpits of the four craft were eight individuals who possessed a common interest in aviation and were bound together in friendship, as well as in blood – for onboard this sojourn were four father and son combinations. The Piper J-3 Cub was piloted by Dr. Bob Poling and his son, David. The blue and white Aeronca ‘Champ’ had on board Dave Long and his son, Tim. Piloting the bright orange and yellow Aeronca was Harold Armstrong and his son, Bob. The black and white star burst aircraft was occupied by the author and his son, Mark Armstrong. Harold and Bill are brothers so there existed a further family relationship. Additionally, Bob Poling and Dave Long are cousins.

This trip had been long planned and was eagerly awaited. The destination was Oshkosh, Wisconsin, and the week long huge annual air show, sponsored by the Experimental Aircraft Association, that is held at Wittman Field adjacent to the city. Oshkosh is a name familiar for its production of trucks and heavy equipment as well as for Winnebago motor homes. The airfield is located near the western edge of Lake Winnebago and just south of the town of Oshkosh. Green Bay lies to the northeast and Milwaukee to the southeast of Wittman Regional Airfield. Six of the eight on board the four aircraft had made previous trips to the Oshkosh Air show, but for my son and me, this was our first to that large event.

The four aircraft were extremely light weight, of tubular construction, covered with a cloth fabric that enabled a small four cylinder engine to power the airframe at speeds just a bit faster than current interstate highway travel by automobile. None had an electrical system and therefore with no mechanical starter all had to be started by hand, so that the name ‘Armstrong starter’ was clearly appropriate. Each aircraft fully loaded with fuel, pilots, minimal cross country items, and clothing essential for a week’s stay, came close but did not exceed 1,300 pounds. The Aeroncas have a single 13 gallon fuel tank and the J-3 Cub a bit more. Burning fuel at a rate barely over four gallons per hour meant that the maximum leg of a flight could not exceed three hours, but practical application resulted in legs of one and one-half to two hours. We were not in any great hurry and planned leisurely segments of the trip so that we could travel the nearly 700 miles without taxing ourselves to any great degree. Our intent was to stop at small airfields, with refueling capability, away from the congested areas, and if the fields had older flying equipment to view, so much the better.

The departure from the Greater Cumberland Regional Airport was undertaken only after a good overview of the weather outlook. These aircraft, of necessity, are flown in fair weather conditions, not equipped with instrumentation allowing for flight in clouds. The weather picture looked good, take off was made from Cumberland, and the four aircraft were formed in a loose, comfortable formation as the occupants anxiously began the trip. We had definite airfields where we wished to stop, but knew that a great deal of flexibility was in order, by virtue of changing weather conditions and other factors. Our first stop was at Alderman Field, St. Clairsville, OH, and some fifteen miles west of Wheeling, WV. This was a quaint field, possessing numerous artifacts with early aeronautical items within the old barn-like operations building. This leg was 119 statue miles in length, but our next was shorter with a fuel stop at Wynkoop Airport, just south of Mt. Vernon, OH, a distance of 85 miles. By this time the higher mountainous terrain was behind us and we knew that from here on we would be over flying basically flat land country. After refueling the craft we headed for Bluffton, IN, an airfield adjacent to Interstate Highway 75 in the middle of the flat Indiana territory. This field has a nice, convenient motel and restaurant only 200 yards removed from the area where we would tie down our aircraft. Although we had plenty of daylight remaining, the decision was made to remain here for the night. We had traversed 334 miles in 5.7 hours of flight time, with the prevailing westerly head winds slowing us down considerably. But we had a good start and, with our planned arrival at Oshkosh on July 26, we were complying with our loose schedule.

The formation of four aircraft on an overnight stopover at Bluffton, Indiana, inbound to Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

The navigation methods employed could be termed crude. We all had navigational maps, called sectionals, which allowed for the tried and true method of pilotage and dead reckoning. Three of the aircraft had hand held battery powered radios on board, but they were rarely used and then only for an occasional intra-flight communication. We were not equipped nor did we desire to utilize any of the more modern radar monitored flight following control methods, but rather to stay clear of the high density airports and controlled airspace so that we could proceed from point A to point B unencumbered. A line was drawn on the sectional map and that line was followed by simple reference to the map notations of towns, railways, highways, towers, rivers, lakes, power lines, and other items which gave good clues as to the actual location as the flight progressed along the penciled marking. Prior to each flight segment a decision was made as to who would lead the flight and the desired next stop. Each member, using the tail of the aircraft as a desk, would draw a similar line on his sectional. The leader was fully trusted to get to the next destination but it was also self satisfying to follow along as the route was progressed. Wings level, compass heading held as steady as possible, correction for cross winds if any, finger on the map as the flight progressed northwest – those were the flight leader’s duties as occasional glances left and right affirmed that the other aircraft were in sight and maintaining a semblance of formation integrity.

The three aircraft on the wing of the leader assumed positions with one on the left side and two on the right. The distances apart would vary, some choosing to fly a tight wing position for a period, but generally a loose, comfortable position some 500 to 1,000 feet removed, while easily keeping the flight leader in view. The altitude above the ground varied with the average being around 1,000 feet. Over the flat corn fields and pastures of the Midwest, with not a human in sight, it was not uncommon to position the aircraft low to the surface, passing a couple hundred feet above the slow passing terrain. This allowed for better close-up views of the underlying earth and an interesting look at any passing objects of interest that kept the crew members from becoming bored with the journey.

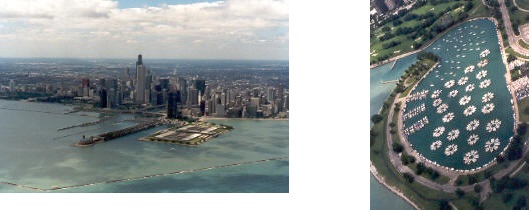

Following a satisfying evening meal and a refreshing night of rest we launched on our second day of travel. The first stop was at Wabash, IN, then on to Hobart, IN, just three miles south of the lower part of Lake Michigan. At that point our route changed from a general northwesterly direction to almost due north as we headed over the large body of water. This was necessary to avoid the over flight of Chicago with its restrictive control of the several large airports in the vicinity. We simply kept the coast line on our left passing abeam the big city while heading northward, keeping about three miles off shore at 2,000 foot of altitude. The Chicago skyline on the clear day was immensely impressive and any who may have stared our way may have thought we were rather a large group of insects out over the water meandering around for who knew what.

The Chicago skyline, photographed from over Lake Michigan, and on the right, a picturesque view of a marina along the coast line, with the boats in a floral arrangement.

When beyond the control zone encompassing Chicago, we turned more westward and back ashore in the vicinity of Waukegan, IL. A stop was made at Kenosha, WI, with its long crossing paved runways, unusual to us as we had heretofore avoided the larger city airfields in our travels. Wanting to get closer to our final destination, we assured via telephone that we had motel reservations at West Bend, WI which would then allow for just a short hop to Oshkosh the following day. Arriving at West Bend, we were glad to be on schedule and retired for the night, planning an early get up and departure.

The Oshkosh air show was to begin on July 27, one day after our arrival date and would attract one million visitors. Nearly 10,000 aircraft from around the world fly in for this enormous event which dictates precise arrival procedures. In our case we would be arriving as no-radio type aircraft and would be required to follow an exact ground path under an approved and well studied approach. Procedures required a mail request with information regarding arrival of no-radio equipped aircraft and prior authorization for entry into the Oshkosh airfield pattern. This we had done several weeks in advance. Further, the no-radio type aircraft had to arrive between the hours of 7:00 and 11:00 am, or, if unable, to wait until the next morning. Our four aircraft departed West Bend as planned at 8:00 am for the last 46 miles to Oshkosh. Harold and Bob, having made several previous trips to Oshkosh, led the last leg. Arrival was shortly before 9:00 am, the prescribed northbound ground track was flown, the proper turns accomplished, light signals from the control tower monitored, a west bound base leg flown, and a landing heading south on a parallel taxiway to the main runway was made in turn by the four small aircraft.

Mission accomplished was the mantra of the morning. We had traveled 673 statue miles in 10.5 hours of flight time in three days. This equated to a less than impressive ground speed of 64 mph, slowed considerably by the generally prevailing western head winds encountered. But we were now at our destination and prepared to spend a few days enjoying the world’s largest non-military air show in the world. Bob, Mark, and I planned to camp under the wings of our aircraft, with the other five staying at dormitories in the college town of Oshkosh. As a result our two aircraft were parked in the designated camping area and the other two fairly far removed to the north. Aircraft were parked over acres and acres of real estate, most of them in grassy areas, but some on the paved portions of the field. Small and large, old and new, home built, kit built, factory new, all kinds of aircraft covered the expansive airfield. These surrounded the multitude of display aircraft on the main center tarmac, ranging from World War I bi-planes to the British Airways supersonic Concorde. In stark contrast to some of the other aerial displays, a lone F-117 ‘Stealth’ fighter, heretofore kept under tight secrecy by the Air Force at an isolated base in Nevada, made a public appearance with fly-bys, and then sat on open display inside a guarded barricade. It was obvious that there was so much to see – now if only the feet and legs would hold up enabling the visitors to observe it all.

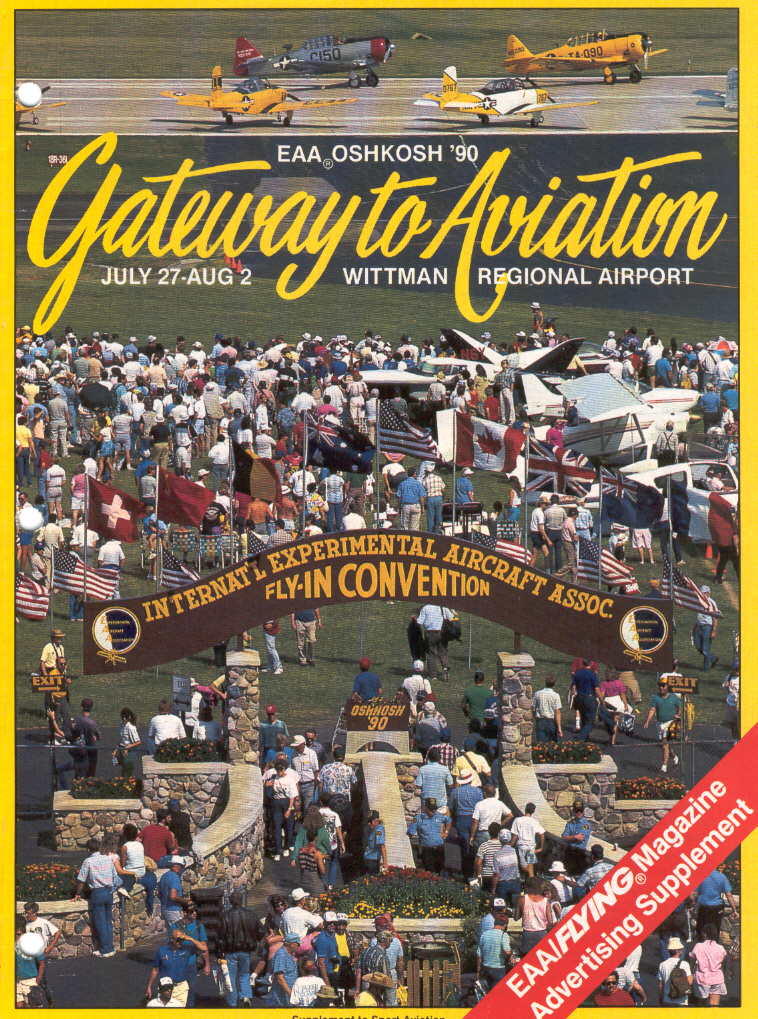

The photograph below depicts a small portion of the huge crowd and some of the aircraft at the 1990 Oshkosh Air Show. This was the official entry point for flight line access.

Oshkosh Fly-In Convention entry point 1990 – Photo from EAA handout.

Each year Oshkosh chooses a major theme for emphasis at the air show. In the year 1990 the theme was the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Britain, which received major sponsorship by Jaguar Car, Inc. This was appropriate since Jaguar produced the bulk of the famous Spitfire fighters instrumental in that heroic battle. There were Spitfires, Hurricanes, and other British aircraft on display, and, yes, lots of Jaguar automobiles. Some of the men and women who participated in that instrumental time were available and reminisced to large crowds displaying keen interest inside a tent set up for the occasion. Winston Churchill heaped high praise on the Royal Air Force in August 1940 during the Axis onslaught of Great Britain when he described the RAF’s gallantry as “their finest hour”. In a never forgotten oration, Churchill went on to state, “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few!”

After securing the aircraft with tie down stakes and ropes in our assigned parking site, a check-in at the registration booth was required to pay for flight line passes and an aircraft camping fee. A detailed schedule of events for the one week show was available for study, which was referenced too little. There was just too much variety of interest so that simply wandering the grounds became the normal action. Every afternoon a three hour air show captured the attention of the multitude of visitors. Daily, the air show was begun by an eight man parachute jump, with the lead jumper displaying the American flag while being circled by four Stearman bi-planes, with their deep humming round engine drone, and trailing red, white, and blue smoke as our national anthem was being loudly broadcast over speakers amongst the crowd. A wide ranging variety of aerial displays followed, probably the most impressive being mass fly-overs of T-34’s, T-6’s, T-28’s, B-17’s, Naval aircraft, numerous other World War II vintage craft, and some jet powered fighters. A reenactment of the attack on Pearl Harbor was part of this display with realistic appearing explosions and billowing smoke, which was undoubtedly a nostalgic setting for the older veterans in attendance. This was a video operator’s dream come true and a photographer’s place of passion.

Hundreds of Warbirds that were flown in World Wars I and II occupied the north end of the flight line display. These historic aircraft were painted with colorful markings relating to units familiar to their owners. These owners, members of the organization EAA Warbirds of America, obviously had a few extra bucks at their disposal that enabled them to buy, fly, and maintain these airplanes, all kept in pristine condition far above their combat ready status during wartime. A highlight of this line-up of aircraft was a Grumman ‘Avenger’, the Navy attack craft flown by President George Bush in World War II. This beautiful two tone blue, three place torpedo delivery aircraft was identical to the one from which the former President was forced to bail out during combat over the Pacific as a twenty year old Ensign.

For the next four days we toured the flight line, viewing aircraft after aircraft and attending forums held in large tents. Jeanna Yeager addressed a large crowd on her participation in the Voyager’s non-stop around-the-world flight. Vendors in the ‘Fly Market’ offered all kinds of paraphernalia. Evening entertainment sessions were set in the Theater in the Woods, a huge pavilion conveniently located in a grove of large oak trees west of the main parking area. Master of Ceremony duties were handled by media personalities David Hartman and Cliff Robertson, who would lead discussions with the likes of Chuck Yeager and EAA founder Paul Poberezny.

A wide variety of food vendors were available throughout the grounds and portable showers were available for the campers who spent the night on the airfield with their aircraft. When the walking become too tiresome a retreat was made to our aircraft and small beach chairs were set up under the shade of our aircraft’s wings allowing for a relaxing break in the action. An Oshkosh radio station offered full time coverage of the event so that it was possible to listen on a transistor radio if far removed from the on site public address system. Portable latrines dotted the area to accommodate the crowd and sufficient garbage receptacles covered the grounds. Contrary to other large gatherings of this type, the grounds were always immaculate. Strewn litter was not the normal situation here – this has always been a strong point of emphasis at Oshkosh, to which all participants can point with pride. Even around the food vendors which accommodated large crowds, all debris was placed in the proper containers. Smoking is never allowed on the flight line or around any of the great numbers of aircraft, which is pleasing to all of the visiting aircraft owners.

The folks that were housed in the college dormitories had better sleeping conditions than Bob, Mark, and I had in our small tents, and they did not have to worry about the rain that fell on two of the nights. But we stayed dry and slept reasonably well on our ground strewn sleeping bags. As campers spending all of our days on the grounds and our nights by our aircraft, we experienced the full flavor of the event. Promptly at 7:00 am the sounding of Reveille, loudly broadcast over the PA system, would awaken any sleepers not up by that time. This was followed by the yodeling of a most talented and dedicated individual, long a fixture at Oshkosh, who treated us to some beautiful renditions of flying terminology in a manner that brought huge grins to all who could hear. Some aviators were attracted to the camping methods simply to be delighted by this yodeler.

Camp site location for Bob, Mark, and the author.

In open fields to the west were located hundreds of campers in mobile homes, vans, and make-shift tents, some of whom had arrived several days before the show began in order to gain the choice up-close sites. An aerial view of the area revealed rows and rows of parked aircraft and a monstrous maze of parked automobiles, as well as fields of campers. Also to the west is located the Experimental Aircraft Association Museum, a veritable collection of aircraft beginning with the 1903 Wright Flyer and progressively displaying aircraft up to modern times. Adjacent to the museum is a grass runway and the home of the Pioneer Airport, with old time hangars housing many flyable aged aircraft with such names as Pitcairn and Pietenpol. To fully appreciate the museum and Pioneer Airport one would need to spend a full day taking in those sights.

There is so much to observe on these sprawling grounds and it is evident that this is a well organized event. The EAA organization is blessed with a large cadre of volunteers who are essential to assuring the smooth running success of Oshkosh. These volunteers aid in parking aircraft, assuring safety by walking the taxiing aircraft’s wings, guarding gate entry points, manning registration booths and first aid stations, driving trolleys back and forth, policing the grounds, and even working in tents that have activities for wives and young children to occupy their time while their men folk ogle aircraft. Hundreds of vendors displayed their wares with so much variety to sell that no one should have left empty handed without a souvenir of remembrance. Our four aircraft were in the category of ‘Antique Classic’ as defined by the EAA and, as a courtesy to the folks attending with those defined aircraft, we were given a plaque with a mounted photograph of each craft in its parked site. Also, the EAA graciously gave each pilot a beautiful glass and pewter embossed mug. The aviator wings affixed to the mug were engraved, ‘EAA Oshkosh ’90 – Showplane Participant’.

During one of my return trips to the aircraft for a bit of rest and shade, there appeared a Post-it note affixed to my Aeronca’s entry door. The note indicated that the visiting stranger had strong desires to me at an agreed time by my aircraft. I complied with his time request and when Gregory Kobliska arrived and introduced himself, he promptly stated, “I used to own this aircraft and got my private license in it!” He then recapped his ownership of the ‘Champ’ in the 1970’s and related in detail work accomplished on the craft during that time. I had known that my aircraft had been purchased by the owner previous to me from a field in Illinois. Aware of the thousands of aircraft parked on the field, in retrospect, I should have asked Gregory, “How many aircraft did you view before coming upon N81855?” N81855 is the tail number identification of my black and white Aeronca, a number that was obviously etched in his mind. Kobliska’s parting thought was, “I sure hated to part with that aircraft.” This is truly indicative that aircraft owners can possess deep devotion to inanimate objects.

A view of a portion of the aircraft and crowd as departure was made from Oshkosh.

The days went by rapidly and before the full realization set in, it was time to depart from this grand event. On the morning of July 31 we packed our aircraft, now a bit heavier than when we arrived, received a required no-radio type aircraft departure briefing, and among a large group of others, left the Oshkosh area. We did make one air crew change. Harold’s wife, Martha, had driven in from Maryland with another brother, Glenn, and Harold opted to return via automobile and relinquish his seat to the younger brother. Glenn, with video experience, used his equipment to record portions of the return of the four ship gaggle. Due to our differing parking locations, we had to depart in two elements for Burlington Municipal Airport, WI, 90 miles to the south, where we then reformed as a flight of four aircraft. From there we headed back out over Lake Michigan to retrace our flight along the Chicago coastline. The next stop was at Starke County Airport, IN, and then onward to land again at Bluffton Airfield, OH where it was decided to spend the evening at this ideal overnight stop.

We had gained speed with favorable winds and knew we could make it home easily in one more day’s effort. The weather cooperated wonderfully, and the departure was made from Bluffton after breakfast, with the next landing at Tri-City Airport at West LaFayette, OH, another of our desired small town airport stops. The mountainous terrain lay ahead and we chose as our next stop Greene County Airport, in Waynesburg, PA. There we had lunch in a small, quaint coffee shop that offered a panoramic view of the rolling countryside. At that point, with but one last leg to fly, we briefed our final flight of the journey. I led the four small classic aircraft, with the now quite tired eight occupants, on the last segment to Cumberland. As we approached the Greater Cumberland Regional Airport, I advised the Unicom radio on the field of the intent to make a low approach with the flight. At a 500 foot altitude, a formation of four tightly flown aircraft made a low pass over the field, advertising to no one in particular that we had returned. In accordance with my briefing at Waynesburg, Bob and Glenn pealed off the right wing to proceed to the home base of Bob’s aircraft near Keyser, WV. Immediately following, Bob and David Poling broke off the left wing for a landing at Mexico Farms, just to the south of Cumberland, where their hangar was located. Dave and Tim Long followed Mark and me to a landing on the Cumberland Airport where we each had homes for our aircraft.

Our journey to and from Oshkosh was complete. Our travels had encompassed nine days, including five on the site at the huge air show. The return trip covered 696 miles in 8.7 hours of flight time, which equates to a ground speed of 80 mph, a considerable improvement over the outbound average of 64 mph. Tallying the totals in both directions revealed a distance of 1,369 miles in 19.2 flying hours and an average ground speed of 71.3 mph. My aircraft was fed 81.8 gallons of fuel which computes to traveling 16.7 miles per gallon, a figure closely shared by my compatriots. Not bad for a little old aircraft, four and one-half decades old, carrying two folks and lots of baggage, on a trip of pure pleasure.

We returned to our homes with pleasant memories of a journey to Oshkosh. The four aged aircraft remained silent in their respective hangars, but if one looked closely, all had a slight smile on their engine cowlings, and if they could converse would gladly state, “We are ready, willing, and able to start our engines, launch into God’s beautiful skies, and go again, if that be your desire!”

* * * * *